Today marks the anniversary of Leon Trotsky’s assassination. Struck down 78 years ago by an ice-pick to the head from a cowardly Stalinist assassin, he soon fell into a coma and died the following day, 21st August 1940. Here we republish an article from the anniversary in 2012, the fight for Trotsky's ideas remain as relevant as ever and we commemorate the life and ideas of this inspiring revolutionary, theoretician and leader.

Watching Trotsky, one would believe that Trotsky was the shadowy mastermind of the revolution, hiding behind Lenin’s public image, the man who created Stalin as his “golem” and then lost control, a man who made himself a monster, obsessed with power and control, surrounded by sex and death — and yet at the same time a puppet of an anti. The Tsaritsyn conflict was only the first stage in the long and ultimately violent confrontation between the two post-Lenin heavyweights of the Bolshevik movement. It finally ended on Aug. The death of Leon Trotsky Leon Trotsky was one of the founders of the Soviet Union and an obvious candidate to replace Lenin after his death. Unfortunately for him, it was Joseph Stalin who came to power, and Trotsky went into a long forced exile that eventually took him to Mexico, where he found asylum. On August 20, 1940.

The attack was no surprise. Ever since Trotsky’s arrival in Mexico, the Stalinist press was busy slandering the Old Man in preparation for an assassination attempt. At the same time, Moscow was waging a massive international campaign against him, infiltrating the movement and, under Stalin’s orders, preparing his death.

Following the end of the Spanish Civil War, Stalinist NKVD agents were dispatched to Mexico to carry out the plans. The first assault had come in May 1940, when Trotsky’s bedroom was riddled with bullets and Robert Sheldon Harte, his secretary-guard, was kidnapped and murdered. Sheldon’s body was later discovered in a lime-pit. Stalin had become desperate in his efforts to eliminate Trotsky, one of the few old Bolsheviks still alive - the rest had been murdered by Stalin during the Purge Trials of 1936-38. These horrendous frame-ups, where the defendants were forced to implicate themselves in lies and terrorist crimes supposedly organized by Trotsky, constituted a river of blood differentiating counter-revolutionary Stalinism from genuine Bolshevism.

Stalin knew that having betrayed the Revolution, he needed to eliminate those who defended and embodied the ideas of Bolshevism and world revolution. First and foremost this fell to Leon Trotsky, who had been driven into exile some eleven years earlier. All the resources of the Russian state were now set in motion to carry out his assassination. Before long, Stalin had murdered several of Trotsky’s co-workers, seven of his secretaries, and four of his children – the latest being his son Leon Sedov in early 1938.

Trotsky was an outstanding revolutionary and theoretician. As early as 1904, he expounded this theory of the Permanent Revolution, which was confirmed in practice by the October Revolution. Trotsky had spent his entire life in the revolutionary movement, led the Petrograd Soviet in 1905, led with Lenin the October Revolution in 1917, created the Red Army from scratch, helped build the Third International, then, fighting against the Stalinist bureaucracy, was cast from power and forced into exile by Stalin.

From Alma Ata, while others capitulated to Stalin, he single-handedly took up the struggle to build the International Left Opposition in the fight for genuine Marxism. He analysed Stalinism as a form of Bonapartism, but based upon a nationalized planned economy. Stalinism was a Thermidorian reaction that arose from the isolation of the Russian Revolution in a backward country, resulting in a massive growth of the bureaucracy in the party and state. Stalin was the figure head of this political reaction to October, who sought to trample over the real heritage of October and pursue the anti-Marxist idea of “Socialism in One Country”.

The struggle between the International Left Opposition and Stalinism was a fight to the death, in the most literal sense. During the Purges of the 1930s, 18 million were arrested on trumped up charges (“enemies of the people”) and sent to labour camps in hostile and extreme environments, out of which some five million would perish, either of starvation, disease or firing squad. Within two years of the 1934 seventh party congress, out of 139 members elected to the central committee, 110 had been arrested. The Red Army was decimated: 13 out of the 19 commanders of the army corps, 110 out of 135 commanders of divisions and brigades, half of the commanders of regiments and most of the political commissars were executed. In 1938, the Polish Communist Party was officially dissolved on the pretext that it was a cover for counterespionage!

“Our old comrade of the Polish party, Schwarzbart, one of the secretaries of the autonomous Jewish district of Birobidzhan, went before the public prosecutors”, recalled Leopold Trepper, the former leader of the Communists working behind enemy lines (the “Red Orchestra”). “He was thrown into prison, where he became almost blind. One morning at dawn he was taken out into the yard and placed before a firing squad. Before he died, he shouted his faith in the revolution, and just as the bullets laid this old communist militant in the dust, from the cells rose the powerful strains of the Internationale.”

Trepper says that “all those who did not rise up against the Stalinist machine are responsible, collectively responsible. I am no exception to this verdict.”

However, he goes on:

“But who did protest at the time? Who rose up to voice his outrage?

“The Trotskyists can lay claim to this honor. Following the example of their leader, who was rewarded for his obstinacy with the end of an ice-pick, they fought Stalinism to the death, and they were the only ones who did. By the time of the great purges, they could only shout their rebellion in the freezing wastelands where they had been dragged in order to be exterminated. In the camps, their conduct was admirable. But their voices were lost in the tundra.

“Today, the Trotskyists have a right to accuse those who once howled along with the wolves. Let them not forget, however, that they had an enormous advantage over us of having a coherent political system capable of replacing Stalinism. They had something to cling to in the midst of their profound distress at seeing the Revolution betrayed. They did not “confess”, for they knew that their confession would serve neither the party nor socialism.” (The Great Game, pp.55-56)

As Trotsky had explained in January 1937, with the announcement of new trials of Radek, Pyatakov and others, “How could these Old Bolsheviks, who went through the jails and exiles of Tsarism, who were the heroes of the civil war, the leaders of industry, the builders of the party, diplomats, turn out at the moment of the ‘the complete victory of socialism’ to be saboteurs, allies of fascism, organisers of espionage, agents of capitalist restoration? Who can believe such accusations? How can anyone be made to believe them? And why is Stalin compelled to tie up the fate of his personal rule with these monstrous, impossible, nightmarish juridical trials?

“First and foremost, I must affirm the conclusion I had previously drawn that the top rulers feel themselves more and more shaky. The degree of repression is always in proportion to the magnitude of the danger. The omnipotence of the Soviet bureaucracy, its privileges, its lavish mode of life, are not cloaked by any tradition, any ideology, any legal forms. The Soviet bureaucracy is a caste of upstarts trembling for their power, for their revenues, standing in fear of the masses, and ready to punish by fire and sword not only every attempt upon their rights but even the slightest doubt of their infallibility. Stalin is the embodiment of these feelings and moods of the ruling caste: therein lies his strength and his weakness.” (Writings, 1936-37, p.121)

He went on to describe the Moscow frame-ups as “the greatest political crime of our epoch and, perhaps, of all epochs.”

In Mexico, in 1937, an independent International Committee of Inquiry was established to examine the Moscow Trials. This inquiry examined all the documents, allegations and evidence, including those from Trotsky. After a rigorous examination of the facts, the Committee declared that the Moscow Trials were a frame-up and that Trotsky and his son were innocent of the charges made against them.

Trotsky was driven from one country to another, where governments closed their doors to him. Only in republican Mexico did he find refuge, and then only to be encircled by hostile agents, trained to do Stalin’s bidding. From here, Trotsky worked continuously to rebuild the forces of genuine Marxism. From here, he laid the basis for a new International.

In August 1936, after completing his brilliant analysis of Stalinism in “The Revolution Betrayed”, and the opening of the frame-up trial of Zinoviev and Kamenev, Trotsky wrote the following about the need to preserve our heritage:

“Reactionary epochs like our own not only disintegrate and weaken the working class and its vanguard but also lower the general ideological level of the movement and throw political thinking back to stages long since passed through. In these conditions, the task of the vanguard is above all not to let itself be carried along by the backward flow: it must swim against the current. If an unfavourable relation of forces prevents it from holding the positions that it has won, it must at least retain its ideological positions, because in them is expressed the dearly purchased experience of the past. Fools will consider this policy ‘sectarian’. Actually it is the only means of preparing for a new tremendous surge forward with the coming tide.

“Great political defeats inevitably provoke a reconsideration of values, generally occurring in two directions. On the one hand the true vanguard, enriched by the experience of defeat, defends with tooth and nail the heritage of revolutionary thought and on this basis attempts to educate new cadres for the mass struggles to come. On the other hand the routinists, centrists, and dilettantes, frightened by defeat, do their best to destroy the authority of revolutionary tradition and go backward in their search for a ‘New Word’.” (Trotsky, Stalinism and Bolshevism)

Trotsky’s struggle was clearly a defence of our revolutionary heritage. Fighting against the stream, he consciously educated and prepared a new cadre for the future revolution. All his time and energy was devoted to this fundamental aim. With the complete degeneration of the Second reformist International and the Stalinist Comintern, the issue of constructing a new international, under extreme difficulties, was paramount. For Trotsky, it was a race against time.

In his Diary in Exile, written in 1935, he explained: “And still I think that the work I am engaged now, despite its extremely insufficient and fragmentary nature, is the most important work of my life – more important than 1917, more important than the period of the Civil War or any other…

“Thus I cannot speak of the ‘indispensability’ of my work, even about the period from 1917 to 1921. But now my work is ‘indispensable’ in the full sense of the word. There is no arrogance in this claim at all. The collapse of the two Internationals has posed a problem which none of the leaders of these Internationals is at all equipped to solve. The vicissitudes of my personal fate have confronted me with this problem and armed me with important experience in dealing with it. There is now no one except me to carry out the mission of arming a new generation with the revolutionary method over the heads of the leaders of the Second and Third International. And I am in a complete agreement with Lenin (or rather Turgenev) that the worse vice is to be more than 55 years old! I need at least about five more years of uninterrupted work to ensure the succession.”

Trotsky had only five more years to live before his murder. He was fully aware of Stalin’s intentions to eliminate him. Stalin had very much regretted the decision to deport him out of reach. These last years were crammed full of articles, letters and advice to the young forces of Trotskyism, as well as the founding of the Fourth International. These were the richest of years as can be seen from his invaluable writings.

Following Trotsky’s tragic death, the Fourth International was destroyed by its inadequate leadership, who made one mistake after another and was consumed with prestige politics. As with Marx, Trotsky had sown dragons but reaped fleas. Nevertheless, the task remains to rebuild the movement, which is being undertaken today by the International Marxist Tendency. Based on the real ideas of Trotsky and the great Marxists, we will finish the task bequeathed by the Old Man.

On this occasion of the anniversary of Trotsky’s assassination, we renew our faith in the world working class and the revolutionaries ideas of Marxism. World revolution is now being put back on the agenda. We are therefore proud to stand on the shoulders of giants. We hold to the words of Trotsky’s final Testament:

'I can see the bright green strip of grass beneath the wall, and the clear blue sky above the wall, and sunlight everywhere. Life is beautiful. Let the future generations cleanse it of all evil, oppression and vileness and enjoy it to the full.”

| Born | Jaime Ramón Mercader del Río 7 February 1913 |

|---|---|

| Died | 18 October 1978 (aged 65) Havana, Cuba |

| Resting place | Kuntsevo Cemetery, Moscow, Russia |

| Other names | Jacques Mornard; Frank Jackson; Ramón Ivánovich López |

| Occupation | Waiter, militiaman, soldier, agent of the NKVD |

| Spouse(s) | Roquelia Mendoza Buenabad |

| Children | 3 |

| Parent(s) | Caridad Mercader, Pablo Mercader Marina |

| Conviction(s) | Murder |

| Criminal penalty | 20 years imprisonment |

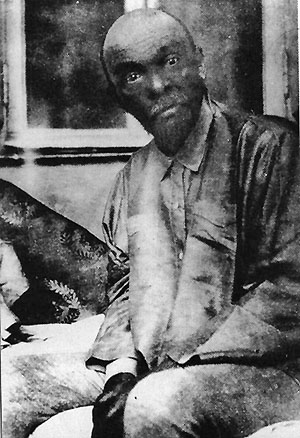

Jaime Ramón Mercader del Río (born 7 February 1913[1] – 18 October 1978),[2] more commonly known as Ramón Mercader, was a Spanish communist and NKVD agent[3] who assassinated Russian Bolshevik revolutionary Leon Trotsky in Mexico City in August 1940 with an ice axe. He served 20 years in a Mexican prison for the murder. Joseph Stalin presented him with an Order of Leninin absentia. His mother participated in the preparation of the assassination, waited for Ramon near the house of Trotsky but escaped to Moscow. With the exception of Ramon Mercader all other persons who participated in the preparation of assassination obtained Soviet awards as well. Ramon was not awarded because nobody could learn how he behaved during the trial and how he would behave in prison.[4]

Mercader was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union after his release in 1961. He divided his time between Cuba and the Soviet Union.

Life[edit]

Mercader was born on 7 February, 1913 in Barcelona to Eustaquia (or Eustacia) María Caridad del Río Hernández, the daughter of a Cantabrian merchant who had become affluent in Spanish Cuba, and Pau (or Pablo) Mercader Marina (b. 1885), the son of a Catalan textiles industrialist from Badalona. Mercader grew up in France with his mother after his parents divorced. She was an ardent Communist who fought in the Spanish Civil War and served in the Soviet international underground.

As a young man, Mercader embraced Communism, working for leftist organizations in Spain during the mid-1930s. He was briefly imprisoned for his activities, but was released in 1936 when the left-wing Popular Front coalition won in the elections of that year. During the Spanish Civil War, Mercader was recruited by Nahum Eitingon, an officer of the NKVD (People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs, an agency preceding the KGB), and trained in Moscow as a Soviet agent.[5]

His cousin, actress María Mercader, became the second wife of Italian film director Vittorio De Sica.

Mercader's contacts with and befriending of Trotskyists began during the Spanish Civil War. George Orwell's biographer Gordon Bowker[6] relates how English communist David Crook, ostensibly a volunteer for the Republican side, was sent to Albacete. He was taught Spanish[7] and also given a crash course in surveillance techniques by Mercader.[8] Crook, on orders from the NKVD, used his job as war reporter for the News Chronicle to spy on Orwell and his Independent Labour Party comrades in the POUM (Workers' Party of Marxist Unification) militia.[8]

Assassination of Trotsky[edit]

In 1938, while a student at the Sorbonne, Mercader, with the help of NKVD agent Mark Zborowski, befriended Sylvia Ageloff, a young Jewish-American intellectual from Brooklyn, New York and a confidante of Trotsky in Paris. Mercader assumed the identity of Jacques Mornard, supposedly the son of a Belgian diplomat.

A year later, Mercader was contacted by a representative of the 'Bureau of the Fourth International.'[9] Ageloff returned to her native Brooklyn in September that same year, and Mercader joined her, assuming the identity of Canadian Frank Jacson. He was given a passport that originally belonged to a Canadian citizen named Tony Babich, a member of the Spanish Republican Army who died fighting during the Spanish Civil War. Babich's photograph was removed and replaced by one of Mercader.[9][10] Mercader told Ageloff that he had purchased forged documents to avoid military service.

In October 1939, Mercader moved to Mexico City and persuaded Ageloff to join him there. Leon Trotsky was living with his family in Coyoacán, then a village on the southern fringes of Mexico City. He was exiled from the Soviet Union after losing the power struggle against Stalin's rise to authority.

Trotsky had been the subject of an armed attack against his house, mounted by allegedly Soviet-recruited locals, including the Marxist-Leninist muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros.[11] The attack was organised and prepared by Pavel Sudoplatov, deputy director of the foreign department of the NKVD. In his memoirs, Sudoplatov claimed that, in March 1939, he had been taken by his chief, Lavrentiy Beria, to see Stalin. Stalin told them that 'if Trotsky is finished the threat will be eliminated' and gave the order that 'Trotsky should be eliminated within a year.'[11]

After that attack failed, a second team was sent, headed by Eitingon, formerly the deputy GPU agent in Spain. He allegedly was involved in the kidnap, torture, and murder of Andreu Nin. The new plan was to send a lone assassin against Trotsky. The team included Mercader and his mother Caridad.[11] Sudoplatov claimed in his autobiography Special Tasks that he selected Ramón Mercader for the task of carrying out the assassination.[12]

Through his lover Sylvia Ageloff's access to the Coyoacán house, Mercader, as Jacson, began to meet with Trotsky, posing as a sympathizer to his ideas, befriending his guards, and doing small favors.[13]

On 20 August 1940, Mercader was alone with Trotsky in his study under the pretext of showing the older man a document. Mercader struck Trotsky from behind and mortally wounded him on the head with an ice axe while the Russian was looking at the document.[14]

The blow failed to kill Trotsky, and he got up and grappled with Mercader. Hearing the commotion, Trotsky's guards burst into the room and beat Mercader nearly to death. Trotsky, deeply wounded but still conscious, ordered them to spare his attacker's life and let him speak.[15]

Caridad and Eitingon were waiting outside the compound in separate cars to provide a getaway, but when Mercader did not return, they left and fled the country.

Trotsky was taken to a hospital in the city and operated on but died the next day as a result of severe brain injuries.[16]

Trotsky's guards turned Mercader over to the Mexican authorities, and he refused to acknowledge his true identity. He only identified himself as Jacques Mornard. Mercader claimed to the police that he had wanted to marry Ageloff, but Trotsky had forbidden the marriage. He alleged that a violent quarrel with Trotsky had led to his wanting to murder Trotsky.

He stated:

... instead of finding myself face to face with a political chief who was directing the struggle for the liberation of the working class, I found myself before a man who desired nothing more than to satisfy his needs and desires of vengeance and of hate and who did not utilize the workers' struggle for anything more than a means of hiding his own paltriness and despicable calculations ... It was Trotsky who destroyed my nature, my future and all my affections. He converted me into a man without a name, without country, into an instrument of Trotsky. I was in a blind alley ... Trotsky crushed me in his hands as if I had been paper.[9]

In 1940, Jacques Mornard was convicted of murder and sentenced to 20 years in prison by the Sixth Criminal Court of Mexico. His true identity as Ramón Mercader eventually was confirmed by the Venona project after the fall of the Soviet Union.[17]

Ageloff was arrested by the Mexican police as an accomplice because she had lived with Mercader, on and off, for about two years up to the time of the assassination. Charges against her eventually were dropped.

Release and honors[edit]

Trotsky Death Agony Of Capitalism

Shortly after the assassination, Joseph Stalin presented Mercader's mother Eustaquia Caridad with the Order of Lenin for her part in the operation.[18]

After the first few years in prison, Ramon Mercader requested to be released on parole, but the request was denied by the Mexican authorities. They were represented by Jesús Siordia and the criminologist Alfonso Quiroz Cuarón. In 1943 Caridad Mercader applied to Stalin personally for her part in the secret operation to release Ramon Mercader.[19] In 1944 she obtained a permit to leave the USSR. However, contrary to the agreed upon conditions, she not only led the attempt of release of Ramon at a distance, but traveled to Mexico, where she was known if not as the mother of Ramon, but as the organizer of the assassination. That undermined an undercover operation that was being prepared to get Ramón Mercader out of jail.[20] Caridad Mercader's presence proved to be counterproductive, because she improved the life of Ramon in prison most significantly but the Mexican authorities tightened security measures, causing the Soviets to abandon their efforts to release Ramon. Though Caridad reported very important things to the Mexican authorities, Ramon served 20 years and 1 day in prison (including the time under initial investigation and trial) according to the initial trial.[20] Ramón, who according to his brother Luis never shared his mother's passion for the communist cause,[21] never forgave her this interference.[22]After almost 20 years in prison, Mercader was released from Mexico City's Palacio de Lecumberri prison on 6 May 1960. He moved to Havana, Cuba, where Fidel Castro's new socialist government welcomed him.

In 1961, Mercader moved to the Soviet Union and subsequently was presented with the country's highest decoration, Hero of the Soviet Union, personally by Alexander Shelepin, the head of the KGB. He divided his time between Czechoslovakia, from where he traveled to different countries, Cuba, where he was the advisor of the Foreign Affairs Ministry, and the Soviet Union for the rest of his life. He married a Mexican named Rogalia in prison after 1940 and had two children. They were declared his and his wife's adopted children, the biological children of Spanish Republicans, after his death.[23]

Ramón Mercader died in Havana in 1978 of lung cancer. He is buried under the name Ramón Ivanovich Lopez (Рамон Иванович Лопес) in Moscow's Kuntsevo Cemetery.[2] His last words are said to have been: 'I hear it always. I hear the scream. I know he's waiting for me on the other side.'[24]

Decorations and awards[edit]

- Order of Lenin, 1940 (in absentia)

- Hero of the Soviet Union, 1961

In popular culture[edit]

- In 1967, West German television presented L.D. Trotzki – Tod im Exil ('L. D. Trotsky - Death in exile'), a play in two parts, directed by August Everding, with Peter Lühr in the role of Trotsky.

- Joseph Losey directed the film The Assassination of Trotsky (1972) featuring Alain Delon as Frank Jacson/Mercader and Richard Burton as Trotsky.

- David Ives' play Variations on the Death of Trotsky is a comedy based on Mercader's assassination of Trotsky.

- A Spanish documentary about Mercader's life, called Asaltar los cielos ('Storm the skies'), was released in 1996.

- A Spanish-language documentary, El Asesinato de Trotsky, was co-produced in 2006 by The History Channel and Anima Films as a joint US/Argentine production, and directed by Argentinian director Matías Gueilburt.[25]

- The Trotsky assassination is depicted in the film Frida (2002), with Mercader portrayed by Antonio Zavala Kugler (uncredited) and Trotsky by Geoffrey Rush.[26]

- Trotskyist veteran Lillian Pollak depicted her friendship with Mercader, then known as Frank Jacson, and the assassination of Trotsky in her self-published 2008 novel The Sweetest Dream.[27]

- A 2009 novel by U.S. writer Barbara Kingsolver, The Lacuna, includes an account of Trotsky's assassination by Jacson.

- Cuban author Leonardo Padura Fuentes' 2009 novel El hombre que amaba a los perros ('The Man Who Loved Dogs') refers to the lives of both Trotsky and Mercader.[28]

- The 2016 film The Chosen, directed by Antonio Chavarrías and filmed in Mexico, is an account of Trotsky's murder, featuring Alfonso Herrera as Mercader.

- Trotsky, a 2017 Russian Netflix series, features Konstantin Khabenskiy as Trotsky and Maksim Matveyev as Mercader, referred to in English subtitles as Jackson, a variant of his pseudonym.

The Trotsky

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^Other sources date Mercader's birth on 7 February 1914

- ^ abPhotograph of Mercader's Gravestone

- ^'The New Trotsky: No Longer a Devil' by Craig R. Whitney, The New York Times, 16 January 1989

- ^L. Mlechin, P. Guontiev. The state corporation of killers. //Novaya gazeta. 08.2020

- ^'Soviet Readers Finally Told Moscow Had Trotsky Slain', The New York Times, 5 January 1989.

- ^randomhouse.co.nz-authors Gordon BowkerArchived 2015-12-22 at the Wayback Machine biography in Random House website

- ^'The Spanish Civil War and the Popular Front', lecture by Ann Talbot, World Socialist Web Site, August 2007

- ^ ab'The Guardian's Prism revelations, Orwell and the spooks' by Richard Keeble, University of Lincoln, 13 June 2013

- ^ abcSayers, Michael, and Albert E. Kahn (1946). The Great Conspiracy against Russia. Second Printing (Paper Edition), pp. 334-335. London, UK: Collet's Holdings Ltd.

- ^Hansen, J. (October 1940). 'With Trotsky to the end,' in Fourth International, volume I, pp. 115-123.

- ^ abcPatenaude, Bertrand (2009). Stalin's Nemesis: The Exile and Murder of Leon Trotsky, p. 138. London, UK: Faber & Faber

- ^Bart Barnes (27 September 1996). 'Pavel Sudoplatov, 89, dies'. The Washington Post

- ^'The fight of the Trotsky family - interview with Esteban Volkov' (1988), In Defence of Marxism website, 21 August 2006

- ^CNN, (11 July 2005). 'Trotsky murder weapon may have been found'Archived 2005-09-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^Deborah Bonello and Ole Alsaker, (20 August 2012). 'Trotsky's assassination remembered by his grandson', The Guardian

- ^Lynn Walsh (summer 1980). 'Forty Years Since Leon Trotsky's Assassination', Militant International Review

- ^Schwartz, Stephen; Sobell, Morton; Lowenthal, John (2 April 2001). 'Three Gentlemen of Venona'. The Nation. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- ^Don Levine, Isaac (1960), The Mind of an Assassin, D1854 Signet Book, pp. 109-110, 173.

- ^The letter to Stalin of Caridad Mercader.

- ^ abHernández Sánchez, Fernando (2006). 'Jesús Hernández: Pistolero, ministro, espía y renegado'. Historia 16 (in Spanish) (368): 78–89. ISSN0210-6353.

- ^Juárez 2008, p. 107. sfn error: no target: CITEREFJuárez2008 (help)

- ^Mercader & Sánchez 1990, p. 101–102. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMercaderSánchez1990 (help)

- ^Arrigabalacha ABC (Spain): Moscow traces of a Spaniard who murdered Trotsky.

- ^Borger, Tuckman (13 September 2017). 'Bloodstained ice axe used to kill Trotsky emerges after decades in the shadows'. The Guardian. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- ^'Documental argentino revive a León Trotsky' ('Argentine documentary revives Leon Trotsky'), El Mercurio, 12 August 2007 (in Spanish)

- ^'Frida' in IMDBase

- ^Pollak, Lillian. The Sweetest Dream: Love, Lies, & Assassination; iUniverse; May 2008; ISBN978-0595490691

- ^'El hombre que amaba a los perros' ('The Man Who Loved Dogs') in Toda la Literatura review, 2009 (in Spanish)

Further reading[edit]

- Isaac Don, Levine (September 28, 1959). 'Secrets of an Assassin'. Life: 104–122. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- Cabrera Infante, Guillermo (1983): Tres tristes tigres, Editorial Seix Barral, ISBN84-322-3016-2.

- Conquest, Robert (1991): The Great Terror: A Reassessment, Oxford University Press, ISBN978-0-19-507132-0.

- Andrew, Christopher; Vasili Mitrokhin (1999): The Sword and the Shield, Basic Books, ISBN978-0-465-00310-5.

- Padura Fuentes, Leonardo (2009): El hombre que amaba a los perros, Tusquets Editores (Narrativa), ISBN978-84-8383-136-6.

- Jakupi, Gani (2010): Les Amants de Sylvia, Futuropolis, ISBN978-2-7548-0304-5.

- Wilmers, Mary-Kay (2010): The Eitingons, Verso, ISBN978-1-84467-642-2.

- International Committee of the Fourth International (1981): How the GPU Murdered Trotsky, New Park, ISBN0-86151-019-4

External links[edit]

Trotsky Death Photos

- Asaltar los Cielos, Spanish documentary about the life of Ramón Mercader, at IMDBase